Great nutrition helps build great kids. It's no surprise that studies link high-quality nutrition to physical health, but research also shows that food plays a role in children's behavior, cognitive performance and academic achievement.

With kids spending so much time—and so many calories—at school, the Greater Watertown Community Health Foundation (GWCHF) partnered with the Johnson Creek School District as it re-envisioned its foodservice program.

Over three years, beginning with the 2018-19 school year, we invested $210,300 in the Johnson Creek School District's effort to transform their school foodservice program. Their mission? "To fuel our children with tasty, nutritious meals made primarily from fresh, whole ingredients and to model and teach food skills to create lifelong healthy habits."

GWCHF dollars supported resources, training and technical assistance along the way, as Johnson Creek School District turned their operation upside down. The process included a kitchen designed to support from-scratch cooking and baking; staff training; and lots of time planning, testing and sourcing.

"Our school board made a long-term commitment to this and recruited a foodservice director who would be able to implement our vision," says Johnson Creek School Superintendent Michael Garvey. "No more cardboard chicken nuggets from the government. We understand the benefits of better meals for our kids, and see it as just another part of doing business. It's an annual investment and the dividends are not counted in dollars."

"Everybody understood the importance of feeding children quality food," says Foodservice Director Kassidy Wright. "I had full support from the school board, superintendent, and principals."

One example of this district-wide support? A change to lunchtime schedules. Principals at elementary and high school rearranged academic schedules to ensure that kids had more time for lunch.

"Not just food but good food and quality food helps our academics," says Middle and High School Principal Neil O'Connell. "What they're eating is reflected in the classroom. The better their food intake, the better their behavior in the classroom."

District support was vital to the program's success. Buy-in from school foodservice team members was also crucial. "At first there was some apprehension," says Wright. "Staff were worried about additional work. But once they started to see the benefits, that they could be more proud of their work, their attitude changed." "I am just so thankful for my staff and all of the hard work they put in every day to make this program a success," says Wright.

District leadership? Check. Foodservice staff? Check. But what about the students themselves (and their tastebuds)?

Creative tactics included a traveling cart that brought breakfast and snacks to the students, regular sampling of new from-scratch food items, marketing on the school website and social media page—even strategically-timed training that tempted educators to taste the new fare on their in-service days.

At the elementary level, they implemented "Try-It Thursdays." "It was a great way for students to try new foods," says Elementary Principal Melissa Enger. "For some, it might be the only time they're getting such nutritious foods. The kids really loved that."

Taste testing aside, there were also new skills to learn. "The garden bar was new," says Wright. "The younger kids needed to learn how to serve themselves. Some of them were just mounding their plates with carrots. They needed guidance and education on how much to take. It was a great learning opportunity."

The fledgling program was dealt a huge blow when schools went to at-home, virtual learning during the pandemic. On the plus side: school breakfast and lunch were temporarily free for all students (removing a barrier to participation for students of all ages). But the meals now needed to reach students, necessitating huge changes in prep, packaging and delivery.

One advantage for Johnson Creek School District? Small size and strong leadership helped them remain agile. They adapted, and adapted again during this challenging time. They leveraged an underutilized bussing contract (that was still being paid for) to aid with delivery, extra kitchen staff which minimized overtime and stress, and help from outside the foodservice program.

"We'd help them load the busses," recalls Garvey. "All these meals, marked by family name and address."

"Some school districts were struggling to provide the bare minimum, while we were making fresh lunches and breakfasts and delivering them," says Wright. "It was a great chance to impress parents."

From the time of pandemic-related school closure in March to the end of the school year in June, they delivered 35,000 meals, averaging 800 meals a day delivered to children.

Post-pandemic, supply chain issues continue to impact school foodservice across the nation. According to a USDA survey released in March 2022, some 92% of school meal programs are experiencing challenges due to supply chain disruptions. Products are not available, orders are arriving with missing or substituted items, and shortages of cooks, food prep personnel, drivers and maintenance staff continue.

"We've had plenty of supply chain issues," says Garvey. "We've had a milk plant closure, a bread company that couldn't get wheat, and a strike at one of the plants. When that happens, we've just figured out how to go somewhere else."

In Johnson Creek, the agility and adaptability of the program, along with some government waivers allowing them to, say, purchase whole cows directly, has meant better outcomes.

"We rely less on prepackaged food," says O'Connell. "We are fortunate to have more options than a typical school foodservice setup."

"Some districts are so tied to their foodservice providers, or have complicated bidding processes," says Garvey. "Purchasing our own cows was a little less expensive, but it was also better quality and we feel great about supporting local farmers."

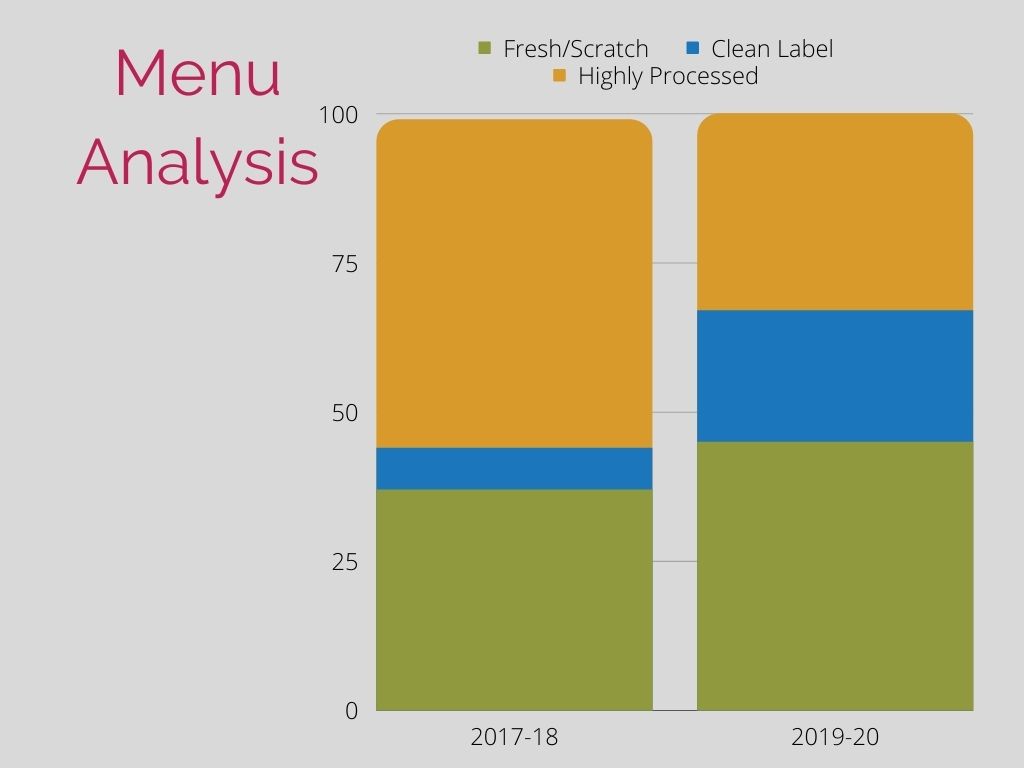

The program uses the School Food Institute, Chef Ann Foundation framework for assessment and planning. One key measure is simply looking at the amount of processed versus fresh food being served. As you can see, highly processed foods such as white bread, canned fruit and processed meats made up less than 30% of Johnson Creek School District's menu in the 2019-20 school year.

"Today our menu offered corn dogs and homemade pulled pork," says Wright. "Everyone chose the from-scratch pulled pork. And we're going to continue to trend those processed foods like corn dogs downward in coming years."

What does student participation look like? Compared to 2017/18 (before the program began), student participation has increased by 43% for lunch, and 127% for breakfast. While COVID has implications for this data, the overall upward trend is undeniable.

"The kids eventually figured out what we were serving them was good for them and delicious," Wright continues. "They were so used to typical frozen and processed food. Now they're excited about homemade shepherd's pie."

To date, the foundation has invested more than $14 million in its five strategic, child-focused priorities:

To learn more about the Foundation and supported initiatives, visit www.watertownhealthfoundation.com or Facebook at Greater Watertown Community Health Foundation.